In new research, scientists confirm that an anti-cancer drug reverses memory deficits in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. (Credit: © fergregory / Fotolia)

The research, funded by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association, reviewed previously published findings on the drug bexarotene, approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in cutaneous T cell lymphoma. The Pitt Public Health researchers were able to verify that the drug does significantly improve cognitive deficits in mice expressing gene mutations linked to human Alzheimer’s disease, but could not confirm the effect on amyloid plaques.

“We believe these findings make a solid case for continued exploration of bexarotene as a therapeutic treatment for Alzheimer’s disease,” said senior author Rada Koldamova, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health.

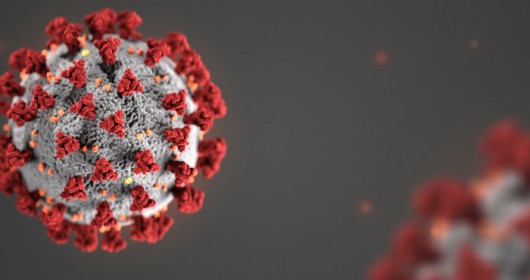

Dr. Koldamova and her colleagues were studying mice expressing human Apolipoprotein E4 (APOE4), the only established genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, or APOE3, which is known not to increase the risk for Alzheimer’s disease, when a Case Western Reserve University study was published last year stating that bexarotene improved memory and rapidly cleared amyloid plaques from the brains of Alzheimer’s model mice expressing mouse Apolipoprotein E (APOE). Amyloid plaques consist of toxic protein fragments called amyloid beta that seem to damage neurons in the brain and are believed to cause the associated memory deficits of Alzheimer’s disease and, eventually, death.

Bexarotene is a compound chemically related to vitamin A that activates Retinoic X Receptors (RXR) found everywhere in the body, including neurons and other brain cells. Once activated, the receptors bind to DNA and regulate the expression of genes that control a variety of biological processes. Increased levels of APOE are one consequence of RXR activation by bexarotene. The Pitt researchers began studying similar compounds a decade ago.

“We were already set up to repeat the Case Western Reserve University study to see if we could independently arrive at the same findings,” said co-author Iliya Lefterov, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor in Pitt Public Health’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health. “While we were able to verify that the mice quickly regained their lost cognitive skills and confirmed the decrease in amyloid beta peptides in the interstitial fluid that surrounds brain cells, we did not find any evidence that the drug cleared the plaques from their brains.”

The Pitt researchers postulate that the drug works through a different biological process, perhaps by reducing soluble oligomers which, like the plaques, are composed of the toxic amyloid beta protein fragments. However, the oligomers are composed of smaller amounts of amyloid beta and, unlike the plaques, are still able to “move.”

“We did find a significant decrease in soluble oligomers,” said Dr. Koldamova. “It is possible that the oligomers are more dangerous than the plaques in people with Alzheimer’s disease. It also is possible that the improvement of cognitive skills in mice treated with bexarotene is unrelated to amyloid beta and the drug works through a completely different, unknown mechanism.”

In the Pitt experiments, mice with the Alzheimer’s gene mutations expressing human APOE3 or APOE4 were able to perform as well in cognitive tests as their non-Alzheimer’s counterparts 10 days after beginning treatment with bexarotene. These tests included a spatial test using cues to find a hidden platform in a water maze and a long-term memory test of the mouse’s ability to discriminate two familiar objects following introduction of a third, novel object.

Bexarotene treatment did not affect the weight or general behavior of the mice. The drug was equally effective in male and female mice.

Source: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/05/130523143541.htm

Comments are closed.